Interview: Trey McIntyre

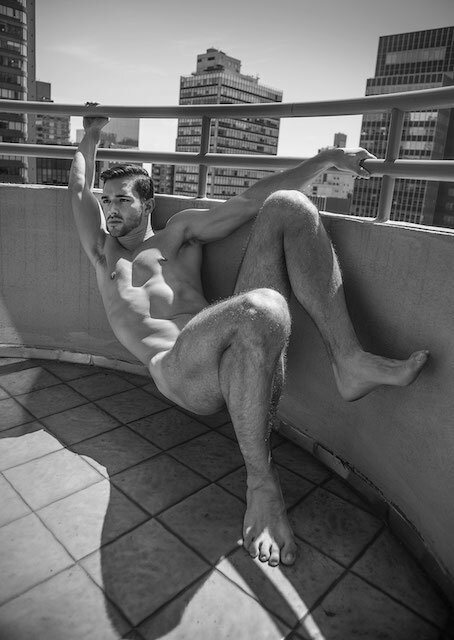

Western Photography Guild had the recent pleasure of interviewing choreographer and dancer Trey McIntyre. A Kansas native, Trey trained in dance at both the North Carolina School of Arts and Houston Ballet Academy. Since then Trey has become a force in ballet and contemporary dance producing over 100 works and receiving numerous awards. Trey is also a creative and accomplished photographer whose focus is typically the male form. Trey features his photography on social media and Patreon.

Consider supporting Trey and his photography at Patreon.

Photograph © Trey McIntyre

WPG: What draws you to photography as an artistic outlet?

TM: Working as a choreographer keeps me in the ephemeral. It’s one of the things that’s beautiful about dance, but ultimately is disappointing. It goes away. Making a photo gives me a tangible thing. Something I can show for my work. There’s an ‘object’ to hold up and say “this is the best of this moment.”

WPG: Many of your models are dancers. To convey movement with still photography can be challenging. How do you approach this challenge?

TM: I think of myself as somewhat of a journalist. I do most everything I can to keep a shoot from feeling like a shoot. I want to create an environment where a collaborator feels they can just ‘be’. Often the most subtle and unconscious movements are the most telling and emotionally moving… so I shoot mostly in the cracks… the in-between moments. However, working with dancers has added benefits. We have a common language and can speak about movement concepts in-depth. Oftentimes I will come up with some kind of movement puzzle that is not about hitting a perfect moment, but rather using one's physical intelligence so a model is able to get lost in the moment.

WPG: What are your challenges creating art in the era of COVID-19?

TM: Even though photographing allows for physical distance, I find that just having the parameter of staying apart is awkward. I think part of the goal is intimacy. Being seen in honesty. And it’s already a big barrier to leap for someone to be seen naked. I’ve done some work via Zoom. I think new mediums are interesting to explore, but I haven’t found the reason for them yet. Not giving up though!

WPG: You frequently post a model Q&A with your photo sets. Why is it important to share your model’s stories?

TM: There is a tendency to depersonalize and objectify the naked body and I seek to do something different. Giving insight into the lives of the people we are seeing helps give context that these are humans with backgrounds and lives.

Photograph © Trey McIntyre

WPG: You clearly encourage collaborative relationships with your models. How do you believe this approach impacts finished works?

TM: So much of a great photograph is about the person feeling comfortable or at least present in their own skin. Having collaboration and say-so in what we are doing goes a long way to making this possible. It also helps open me up and pushes me in new directions so that I’m always learning from each shoot.

WPG: You once mentioned that with choreography, you sometimes bring a piece of music into the room and work from instinct. How do you approach a photo shoot?

TM: It’s quite similar in a lot of ways. I will often meet and speak to a model for the first time when we begin to shoot. I just start reacting to them and who they are and talking to them about ideas in that moment. Other times I have conversations ahead of time and ask a lot of questions about them and who they are and their reasons for wanting to do the shoot in the first place. Sometimes we just dive right in and start creating, sometimes we spend a great deal of time talking and getting to know each other and then the shoot evolves organically from there.

WPG: Facebook and Instagram famously and regularly censor photography featuring the male body while images featuring female bodies is provided greater latitude. Has censorship affected your art or your ability to promote it?

TM: Absolutely. I’ve found the censorship to be arbitrary. I suppose any platform can draw whatever parameters they like, but it’s impossible to play along when they keep moving the goalpost without saying they are doing it. It’s one of the reasons I love Patreon. They have boundaries but are transparent about it. They work with creators to build and support the art they are making.

Photograph © Trey McIntyre

WPG: From what do you draw photographic inspirations?

TM: My inspiration usually comes from the person I’m working with. I really think of all my work as a kind of portraiture and trying to help reveal something honest about the person. It’s a beautiful thing to see happen for someone when we get it right. I am now moving into more theatrical and narrative based photography so I am constructing scenes ahead of time and building sets to support an idea. But even within these photographs I want to make space for the real person that I’m working with to appear in the finished product.

WPG: You’ve spent many years living, creating and presenting in traditionally conservative parts of the country. Do these environments inspire or suppress your creativity?

TM: This is a great question. I would say it does both. There is a real creativity that comes from the conflict and finding common ground with people who think differently than I do. It pushes me in new directions and changes who I am. I always want to be learning. But then conservative areas can tend to have a smaller artistic community. And when I had a dance company in Idaho for example I spent a lot of time thinking about what was best for the community and my contribution to it. This didn’t always necessarily allow me to explore as far creatively as I would have wanted to.

WPG: Early photographers of the male physique, such as Don Whitman, frequently risked police raids and jail time when presenting their visions of art. Do you find any lessons to be learned from those earlier times?

TM: Yes. Art is dangerous because it can speak to and unearth the parts of ourselves that we don’t usually look at. The things below the surface. It’s an artist’s job to be brave and push boundaries not for the reason of making people uncomfortable but for the journey and hard work of uncovering and revealing the truth. This is what makes art important and that’s worth the risk.

Photograph ©Trey McIntyre

WPG: I heard you once described as “high powered chill.” What does that mean to you?

TM: This is a nickname given to me by a dancer I’ve worked with. I think the high-powered part comes from being a leader and making sure everyone understands that you’ve got their best interest in mind and that you’re in control of things and it’s all going to be OK. But I don’t tend to get worried about very much and I certainly don’t lead through intimidation. I’m chill because I trust that what is supposed to happen, will happen.

WPG: You made a comment once regarding “a valuation and embrace of art in today’s world.” Do you believe our culture adequately prioritizes and encourages art in everyday life?

TM: I think sometimes once something is labeled as art, our culture begins to devalue it. I saw a survey just recently about who Americans think are essential workers right now. 'Artists' came up as the least essential. But I think this comes from a misunderstanding and limited thinking about what art is. In fact, the majority of what people have occupied their time with during quarantine has been art. Film, music, television, pornography. These are all things born from a great deal of creative thought, practice, and discipline. Perhaps the fact that these things are meant to bring us joy or at least feeling Is the reason we value them less. Valuable things should be hard. A hard day's work should not relate to your joy but instead be your burden. I also think that as a culture we don’t value the artist in each person. Those parts are frivolous and do not relate to a struggle for survival. But our artist-self is a representative of our creative thinking. It’s the thing that’s going to solve the big problems that we are facing. It’s the voice we use to express crucial parts of ourselves and get us connected to our most realized, loving selves.

WPG: How do your Patreon patrons help you reach your creative goals?

TM: Honestly at this point my photography wouldn’t be possible without them. Financially, they make the expensive work of these photographs possible. They fund it. But they also provide the energy and curiosity that I draw from to keep doing it. I love hearing their comments and perspectives on the work. I love their questions and their interests In the collaborators I work with. It keeps me from feeling like such a solitary artist to know that I have this community.